From the wheel to the light bulb, innovation has played a central role in the story of human civilization. But history’s inventors also left behind a trail of misfires, failures, and downright disasters. Here are five ideas that promised to make life better, safer, or more efficient, but turned out to be spectacular flops.

Baby Cages

In the early 20th century, crowded cities such as New York and London grappled with widespread tuberculosis. At the time, one common treatment was fresh air, prescribed by figures including the influential pediatrician Luther Emmett Holt. In his 1894 book, The Care and Feeding of Children, Holtwrote that babies exposed to fresh air enjoyed better appetites, brighter cheeks, and improved health.

Enter the baby cage — a wire enclosure fastened to an open window, which allowed apartment dwellers to suspend infants several stories above city streets to “air them out.” The first U.S. patent was granted to Emma Read of Spokane, Washington in 1922, though the idea had circulated earlier. The baby cage briefly caught on, notably among members of the Chelsea Baby Club in London. Even Eleanor Roosevelt used one for her infant daughter, Anna, until a horrified neighbor threatened to call the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. Baby cages declined in the second half of the 20th century, largely due to safety concerns.

X-Ray Shoe Fitters

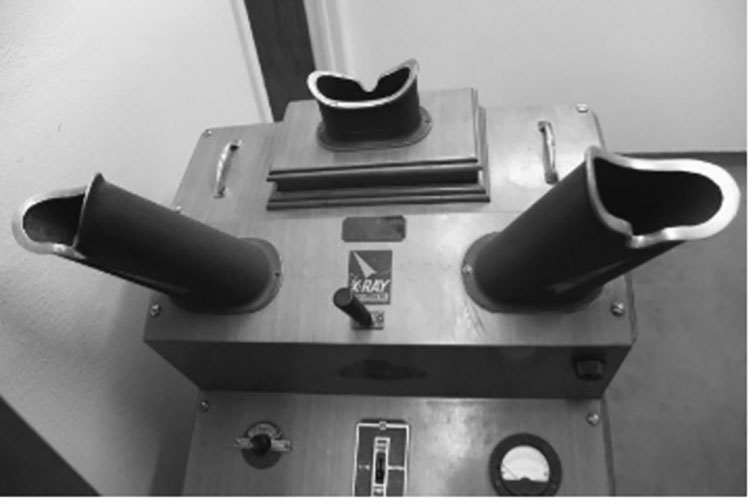

In the 1940s and ’50s, shoe stores across the U.S. offered customers a peek inside their shoes. The shoe-fitting fluoroscope was a wooden box that displayed real-time moving X-ray images of customers’ feet. Invented by Boston physician Jacob Lewis in 1919, the device was originally designed to diagnose foot problems in World War I veterans, and was repurposed for retail use after the war.

Though the X-ray technology was real, the device was essentially a marketing gimmick to help shoe sellers boost sales by lending the fitting process a scientific veneer. But that was the least of the invention’s issues — the fluoroscopes emitted dangerous doses of radiation that far exceeded the maximum safe daily dose. As a result of growing awareness around the dangers of radiation, shoe-fitting fluoroscopes were banned by the late 1950’s.

Thomas Edison’s “Little Monsters”

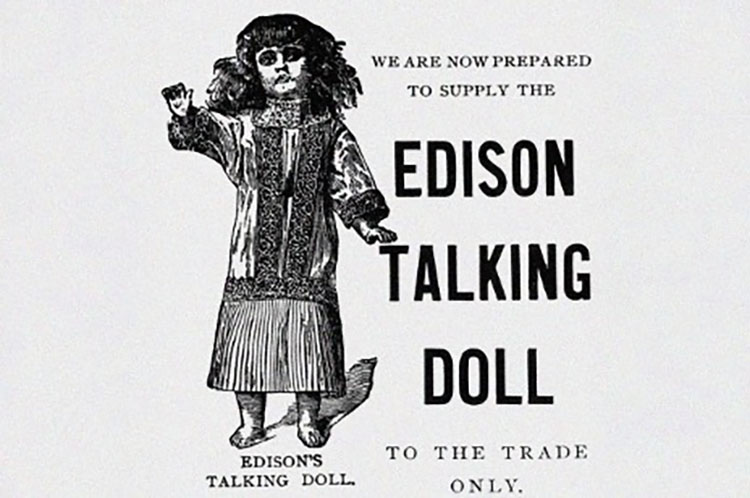

Even the illustrious Thomas Edison had his flops. In 1890, the inventor unveiled the world’s first talking doll, a technological milestone that combined phonograph technology with the classic toy. The 4-pound, 22-inch doll had a porcelain head, wooden limbs, and a tin torso that housed a miniature phonograph. Turning a crank on the doll’s back played wax recordings of nursery rhymes such as “Mary Had a Little Lamb” and “Jack and Jill.”

Unfortunately, Edison’s dolls didn’t speak so much as screech. Due to the low recording volume, the women voicing the rhymes were required to scream into the recorder, resulting in creepy recordings that upset customers. The dolls were also plagued by durability issues and were prone to breaking. Parents complained, children were terrified, and many of the 2,650 dolls sold were returned. Within weeks, Edison withdrew them from the market, ruefully calling them his “little monsters.” Today, Edison’s “monsters” are considered rare collector’s items and have been displayed at the Smithsonian.

The Isolator

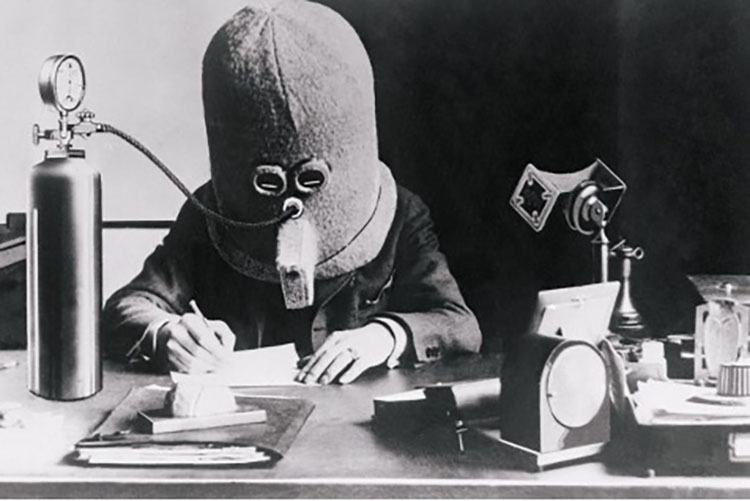

Science fiction pioneer Hugo Gernsback — founder of Amazing Stories magazine and namesake of the Hugo Awards — was also a prolific inventor. In 1925, he introduced one of his strangest creations: the Isolator, a helmet designed to eliminate distractions and maximize focus.

Made of wood and felt, the helmet completely enclosed the wearer’s head, leaving only narrow slits for vision. After realizing that people became drowsy inside the helmet after 15 minutes, partly due to oxygen deprivation, Gernsback added an oxygen tank connected to the helmet by a tube. He claimed the device was 75% efficient and predicted it would be a “great investment” for anyone in need of focus. Though the Isolator never caught on, its spirit lives on in noise-canceling headphones and focus apps.

Anti-Bandit Bag

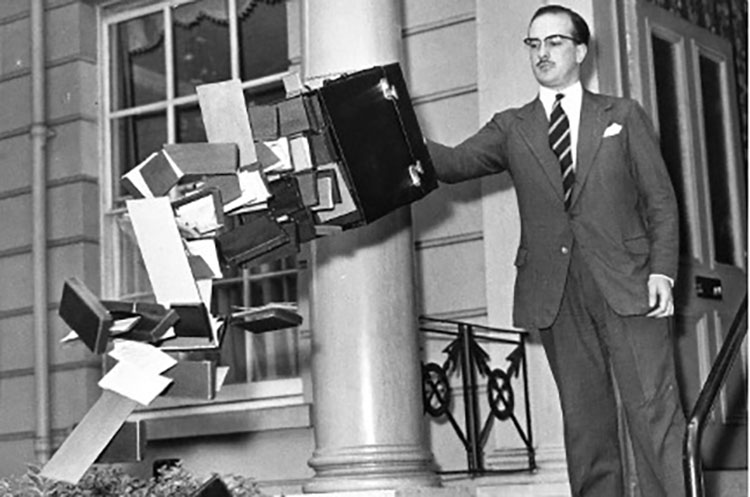

In the 1950’s and ’60s, inventors sought clever ways to foil thieves — and few were as dramatic as the Anti-Bandit Bag. One of the most famous versions was debuted by French Canadian inventor John H. T. Rinfret in 1963. Rinfret, inspired by his own experience of being robbed, designed a bag with a spring-loaded handle, which enabled the carrier to launch the bag’s contents all over the place in the event of a robbery. Other anti-bandit bags spewed smoke and dye or triggered shrieking alarms when snatched. One model, aptly named the “Arrestor,” clamped onto the thief’s hand and blasted out three 12-foot telescoping metal rods, preventing the robber’s escape. None of these designs reached mass production, likely due to their unwieldiness, dubious efficacy, and potential to be triggered accidentally