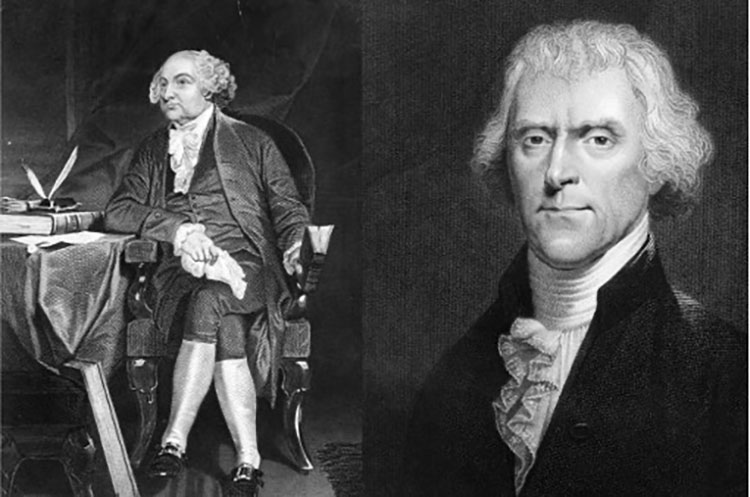

1800: John Adams vs. Thomas Jefferson

If anything proves that partisan politics and electoral machinations are nearly as old as the United States itself, it’s the election of 1800, when Federalist Party incumbent President John Adams sought reelection against Democrat-Republican Vice President Thomas Jefferson. The already-bizarre premise of opposing parties holding the presidency and vice presidency was made possible at the time by a law stipulating that the presidential candidate who earned the second-most number of electoral votes became Vice President. In the election of 1796, Jefferson lost the presidency to Adams by only three votes, and the 1800 election was a rematch between the political rivals.

That time, with another narrow margin likely, both parties turned toward influencing electors, whose votes decided the winning candidate in states where there was not yet a popular vote. Jefferson wrote of his intent to sway electors in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey in a letter to James Madison. Federalist Senator Charles Carroll accused Jefferson and his supporters of also attempting to use “arts and lies” to manipulate votes in Federalist-leaning Maryland. From there, the accusations, well, escalated. Jefferson-supporting pamphleteer James Callendar claimed that John Adams was a hermaphrodite. Federalist newspapers accused Jefferson of maintaining a harem at Monticello.

When the votes were finally cast, the election ended in a tie between Jefferson and… his intended running mate, Aaron Burr. How? Each elector had two votes to cast, but there was no distinction at the time between a vote for President versus a vote for Vice President. Casting one vote for Jefferson and one vote for Burr was in effect a vote for each as President. The Constitution called for resolving this tie between the Democrat-Republican candidates with a vote in the House of Representatives, which was controlled by, you guessed it, the Federalist Party.

The task at hand was to vote on who, between Jefferson and Burr, would be President, but the Federalists saw an opportunity to seize power, either by delaying the proceedings past the end of Adams’ term, or attempting to invalidate enough votes to give Adams the majority. Others advocated for supporting Burr. Between February 11 and February 16, 35 rounds of voting took place, each ending in deadlock. Finally, after much lobbying by Alexander Hamilton against Burr, the 36th ballot resulted in Jefferson being appointed President. In the wake of the turbulent election, the 12th Amendment was ratified in order to prevent a repeat ordeal in 1804.

1840: William Henry Harrison vs. Martin Van Buren

If William Henry Harrison is known today, it’s for the obscurity of his mere 31 days in office. But the campaign leading to his presidency was a rollicking and often rowdy phenomenon that sparked a voter turnout of more than 80%, an increase of nearly 23 percentage points from the previous election.

The election pitted Harrison and running mate John Tyler of the upstart Whig Party against incumbent Democratic President Martin Van Buren during a period of economic strife caused by the Panic of 1837. Harrison’s campaign played off of his military fame for his victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe, with the slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.” It also attacked Van Buren with accusations of living in aristocratic luxury. The Van Buren campaign and its supporters countered by painting the 67-year-old Harrison as too elderly and frail for the presidency. An editorial in the Baltimore Republican mocked Harrison with the line, “Give him a barrel of hard cider, and settle a pension on him… he will sit the remainder of his days in his log cabin by the side of the fire and study moral philosophy!”

The Whigs, however, embraced the hard cider and log cabin imagery, and built the rest of the campaign around it. They leaned into the association with the “everyman,” and organized cider- and whiskey-fueled mass rallies. There were songs, stump speeches, and all manner of bric-à-brac emblazoned with cider kegs and log cabins. There were also the 10- to 12-foot slogan-covered balls Whigs would roll down the streets while chanting in support of the candidates. It all led to Harrison shellacking Van Buren in the election, albeit not quite as might be expected: The lopsided victory was in the Electoral College, 234 to 60, but the popular vote margin was only about 150,000 votes. No need to pity Van Buren, though. He later remarked, “The two happiest days of my life were those of my entrance upon the office and my surrender of it.”

1872: Ulysses S. Grant vs. Horace Greeley

Incumbent President Ulysses S. Grant’s Republican Party was beginning to fracture leading into the June 1872 National Convention. A reform wing calling itself Liberal Republicans had held its own convention the previous month, nominating New York Tribune founder and editor Horace Greeley as its candidate. Overestimating the power of this new faction, the Democratic Party refrained from nominating its own candidate and instead threw its support behind Greeley, despite Greeley’s history of pointed criticism of the Democratic Party.

Almost immediately, Greeley was lambasted in the press. The New York Times called the Democratic Convention that nominated him “the ghastliest of political shows.” Political cartoons were especially harsh, depicting him as mousey or infantile. Greeley soldiered on, making campaign stops in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana between September 19 and 29, and giving nearly 200 speeches in that short span. Unfortunately for the candidate, his running mate Benjamin Gratz Brown completely undermined that effort by giving an incoherent drunken speech at Yale, and then fainting during an event in New York City. The Greeley campaign never really mounted a serious threat to Grant. “I have been assailed so bitterly that I hardly knew whether I was running for the presidency or the penitentiary,” Greeley lamented. Grant won reelection easily with 55.6% of the popular vote. In a bizarre and tragic twist, Greeley died on November 29, before the Electoral College could cast its ballots. Because of this, the 63 votes he would have earned were dispersed among other candidates. It remains the only time in U.S. history that a candidate has died in the interim between the popular vote and the Electoral College vote.

The 1872 election was also notable for another reason: Though not a legal candidate (she was under 35 years old), Victoria Woodhull also ran in the 1872 election, making her the first woman to campaign for President of the United States.

1964: Lyndon B. Johnson vs. Barry Goldwater vs. a Fabricated “Jewish Mother”

The 1964 presidential election took place less than a year after the assassination of John F. Kennedy; the Vietnam occupation was approaching its midpoint, and segregationist Alabama Governor George Wallace was running a primary campaign in the northern U.S. on a platform of outright racism. Into this fraught atmosphere stepped a wisecracking independent write-in candidate named Yetta Bronstein, with slogans such as “We need a Jewish mother in the White House,” A mink coat in every closet,” and “If you want simple solutions, then you gotta be simple.” Calling herself a “Jewish housewife” running for a political party called the “Best Party,” Bronstein managed to attract media attention and invitations for radio interviews, wherein she advocated for increasingly kooky things such as adding “truth serum” to the Senate drinking fountains, and putting a nude photo of Jane Fonda on postage stamps.

Yetta Bronstein was a complete fabrication, though. A character invented by husband-and-wife hoaxers Alan and Jeanne Abel (and played by Jeanne in radio interviews), Yetta was conceived as a way to poke fun at credulous media. In the real world, Lyndon B. Johnson and Barry Goldwater were engaging in some of the most grueling mudslinging yet, culminating in the legendary Johnson “Daisy” campaign ad (officially titled “Peace, Little Girl”), in which a young girl counts petals as a nuclear countdown cuts to a mushroom cloud. Ultimately, Johnson trounced Goldwater by more than 15 million votes in the popular election, and 486 Electoral College votes to Goldwater’s 52. Yetta Bronstein didn’t get a single vote.

1988: George H.W. Bush and “the Seven Dwarfs”

The 1988 presidential election was an open field, with Ronald Reagan finishing out his last term as President. The primary season on the Democratic side included a slate of relative upstart contenders referred to in overtly derisive political commentary as “the Seven Dwarfs”: Bruce Babbitt, Joe Biden, Michael Dukakis, Richard Gephardt, Al Gore, Jesse Jackson, and Paul Simon. On the Republican side, Vice President George H.W. Bush, Bob Dole, Jack Kemp, and televangelist Reverend Pat Robertson were the contenders, escaping a derisive nickname of their own for reasons that are lost to history.

Almost immediately, the Democratic side was beset with paparazzi-style scandals: Early, pre-Seven Dwarfs contender Gary Hart was caught having an affair with a woman who accompanied him on a luxury yacht called, all too on-the-nose, Monkey Business. Another scandal followed when a tape surfaced with footage of Joe Biden speaking at the Iowa State Fair and quoting British Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock without attribution. The resulting furor, and Biden’s subsequent mishandling of it, prompted him to drop out of the race. When TIME magazine reported that the tape came from the Dukakis campaign, the campaign initially denied the report, before eventually coming clean. Dukakis aides John Sasso and Paul Tully also stepped down.

Meanwhile, George H.W. Bush was emerging as the Republican nominee, despite receiving frequent criticism for not communicating the priorities of a Bush presidency (“the vision thing,” as Bush himself rather flippantly put it). Once Dukakis became the Democratic nominee, Bush fully dismissed “the vision thing” in favor of Lee Atwater-aided negative campaigning, successfully painting Dukakis as soft on crime with the viciousness of a Thomas Jefferson-John Adams-era series of invectives.

Another enduringly famous attack ad was one that the Dukakis campaign itself unintentionally provided the imagery for. The ad featured an unfortunately goofy Dukakis video op with the candidate perched upon an M1 Abrams tank and wearing a too-large helmet that looked more Great Gazoo than commander in chief. Bush won the election with 53.4% of the popular vote and a whopping 426 electoral votes.