In previous articles I have attempted to provide some concepts and skills relating to emotional intelligence. Having those can help with having a “difficult conversation,” which is defined as a conversation where three elements are present: high stakes, different opinions, and strong emotions. Sound familiar?

There is nothing inappropriate with having conflicting views about a topic; however, if progress is to be made without alienating people, then we must engage in dialogue or the mutual exchange of ideas. Dialogue can be difficult to achieve but, it is essential if we’re going to keep the community from becoming fragmented.

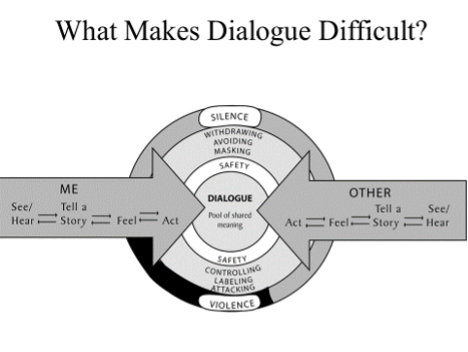

We can walk through the Dialogue Model from Crucial Conversations*, in order to learn how conversations go from dialogue to difficult.

Understanding the Model

In order to have “dialogue,” both parties must feel emotionally safe. This means that both parties feel comfortable sharing their ideas because they know, even if the other party disagrees, he/she is still listening and showing respect. We call that the “pool of shared meaning” (I listen and understand, even if I don’t agree). As you can see, the pool of shared meaning is more wading pool than Olympic size.

What makes us leave the pool and abandon dialogue?

The stories we tell ourselves make us feel “unsafe.”

Our eyes are like video cameras, so we record our interactions with others and interpret them on the spot. Those interpretations result in feelings and subsequent actions we take toward the other person. If those actions appear threatening to the other person, then that person will leave the pool of shared meaning, and dialogue will cease. Interestingly enough, many of us never question the accuracy of the stories we tell ourselves because we are so convinced we are right. Some of the actions that will cause others to vacate the pool include attribution of motives, viewing situations as either/or, confusing an assumption with an inference, and beginning the conversation with “I am right and you are wrong, so let me tell you how you are wrong.”

How do we know if dialogue has ceased?

The most obvious sign is that the other party becomes “verbally violent” by trying to control the conversation through continual interruptions, labelling your ideas as being unworkable, silly, or stupid, and/or ultimately attacking you through name calling. The less obvious approach is silence or avoiding any discussion, masking behavior such as smiling to your face but, cursing you under his/her breath, and ultimately withdrawing from the scene emotionally or physically or both.

How can we stay in dialogue even if we disagree with the other party?

1) Be aware of the story you tell yourself about the other person and his/her motives. Examine your story for assumptions that cannot be verified through fact, realize how big a role your values or beliefs play in formulating your opinion, and that your values may be right for you but not for others. Values are not facts.

2) Instead of consistently pushing your opinion, ask the other person to walk you through how he/she arrived at his/her opinion. Balance advocacy/assertion with inquiry. You may learn more by asking questions. Listen without thinking about what you want to say next.

3) Always show respect for the other person’s opinion, even if you don’t agree.

The bottom line: stay in the pool of shared meaning by making the conversation safe. Start by examining your own story.

*Patterson, Grenny, McMillan, Switzler: McGraw-Hill, 2002.