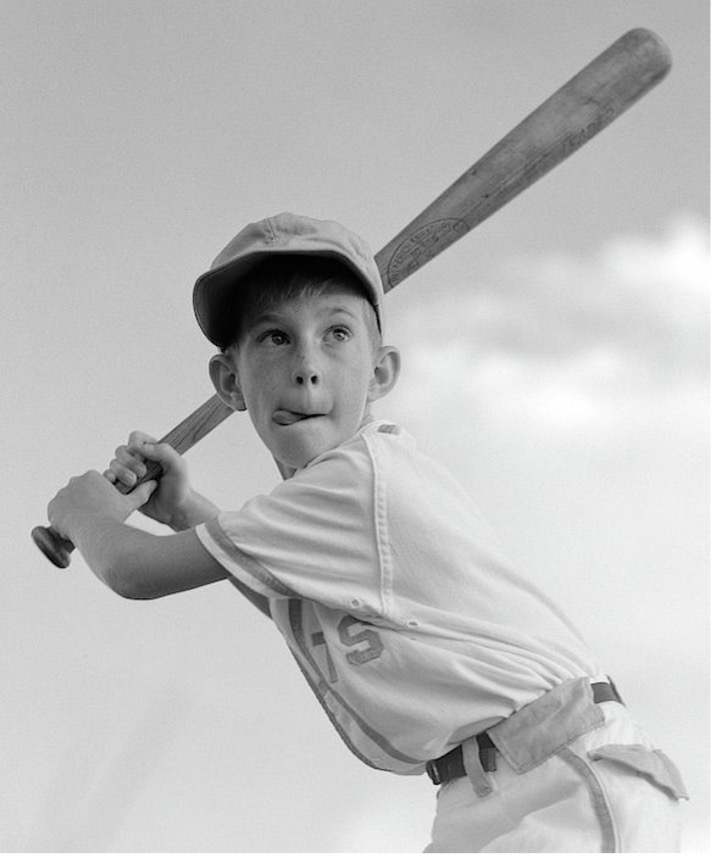

Have you ever wondered why baseball captures the hearts of millions? It’s not just a game; it’s a cultural phenomenon that weaves its way into your life. From the crack of the bat, to the thrill of a home run, baseball has a magic that’s hard to resist. You’ll find fans of all ages filling stadiums, sporting their team’s colors, and sharing moments that turn into cherished memories. It’s the timeless appeal and the suspenseful strategy that make every pitch count.

Let’s dive into why this sport continues to be a home run with fans around the globe by investigating the progression of ancient bat and ball games which led to today’s game.

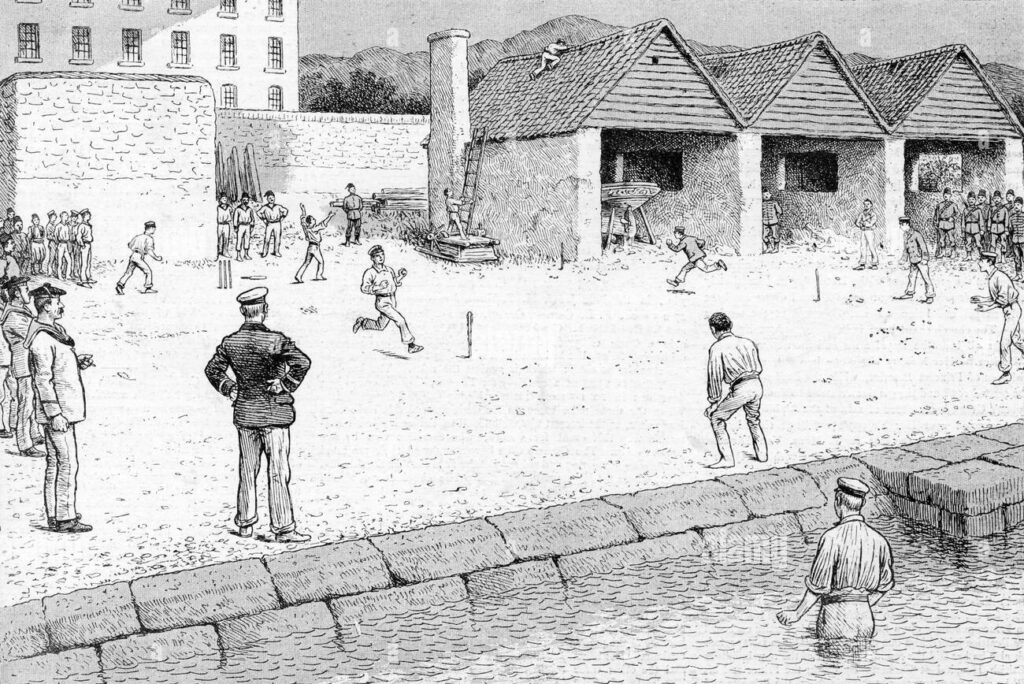

RATHER THAN BASES, AND BATS ARE SHORTER.

Rounders

One such game is Rounders, thought to have originated in Britain, with the earliest documented reference appearing in 1744 in the book A Little Pretty Pocket-Book. However, the game, or something very similar, may have been played even earlier, possibly dating back to the Tudor era, 1486 to 1603, according to some historical sources. The game was formalized with standardized rules, first in Ireland in 1884 by the Gaelic Athletic Association, and then in the UK. Rounders is played on a diamond shaped field with nine players per side. The game uses posts instead of bases, and bats are shorter than used in baseball.

It typically has two innings per game, and an inning ends when all batters have had a turn or when nine outs are made. In Rounders, points, called “rounders,” are scored when a batter hits the ball and successfully runs around all four bases touching the posts with their bat without being put out, or if a player fails to hit the ball but still reaches the fourth post. A “half rounder” can be scored if a batter reaches the second or third post in a single hit without being put out, or if they fail to hit the ball but run to the fourth post. The game remains a very popular intramural sport in Great Britain. To enjoy the Rounders YouTube video, go to: England v Wales Rounders Match – YouTube.

Early Baseball History

Baseball Before We Knew It: A Search for the Roots of the Game is a 2005 book by David Block about the history of baseball. Block investigates the early history of baseball, the debates about baseball’s beginnings, and presents new evidence.

The account, first published in 1905, that Abner Doubleday invented baseball in 1839 was once widely promoted and widely believed. However, this belief was discredited almost immediately. Although the Doubleday myth was never taken seriously by historians, Block showed that the narrative which supplanted it was also deeply flawed. In this accounting, baseball was understood as the derivation of an English children’s game, rounders, but America was allowed to retain patrimony over its national pastime through the assertion that it had been reinvented as a modern sport by the members of the New York Knickerbockers, who codified its rules for the first time in 1845. This idea, according to Block, is wrong in almost every aspect. He argues that baseball was not a product of rounders, and its essential form had already been established by the late 18th century.

Block’s new evidence in the matter includes the first known record of the term “base-ball” in the United States. It came in a 1791 ordinance in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, that banned ballplaying near the town’s new meetinghouse. However, that was not the first appearance of “base-ball” in print. That distinction belongs to an English book, A Little Pretty Pocket-Book (1744). By 1796 the rules of this English game were well enough established to earn a mention in German scholar Johann Gutsmuth’s book on popular pastimes, that described “Englische Base-ball” involved a contest between two teams, in which “the batter has three attempts to hit the ball while at the home plate;” only one out was required to retire a side. The book also predates the rules laid out by the New York Knickerbockers by nearly fifty years. In the book, Block suggests that it was the English game of baseball that had arrived in the U.S. as part of “a sweeping tide of cultural migration” during the colonial period. Once on American soil, the game developed popular regional variations that included “town-ball,” “round-ball,” and the “New York game.”

English baseball was itself the product of a prolonged, nonlinear evolution. “Tut-ball” may have been its immediate predecessor. Stool-ball, an earlier sport, may have been even more influential in the evolution of baseball, and is also a likely parent of cricket, which developed independently. Medieval texts also suggest that baseball’s English antecedents may themselves have descended from Continental bat-and-ball games. An illustration in the French manuscript “The Romance of Alexander” (1344) depicts a group of monks and nuns engaged in a game, thought to be “la soule,” that looks much like co-ed softball. Two other French games, théque and la balle empoisonée (“poisoned ball”), also bear similarities to early baseball. They could have migrated to England. In Block’s words, the field is clear for the French to claim, “parental rights over America’s National Game.”

As Block and other baseball historians have argued, baseball’s development did not form in a linear manner. With the growth in America’s 18th century population and standard of living, a desire for recreational activities expanded.

By the early 1830s, there were reports of a variety of uncodified bat-and-ball games recognizable as early forms of baseball being played around North America. These games were often referred to locally as “town ball,” though other names such as “round-ball” and “base-ball” were also used. With baseball’s growth in popularity, and a desire to play intercommunity games, led to standardizing the regional differences.

In 1845, Alexander Cartwright, a member of New York City’s Knickerbocker Club, produced a code of baseball rules now called the Knickerbocker Rules. The practice, common to bat-and-ball games of the day, of “soaking” or “plugging,” effecting a putout by hitting a runner with a thrown ball was barred. The rules thus facilitated the use of a smaller, harder ball than had been common. Several other rules also brought the Knickerbockers’ game close to the modern one, though a ball caught on the first bounce was an out, and only underhand pitching was allowed.

Thus, baseball’s foundation was established, setting the stage for professional league development. In the 1850s, journalists started referring to baseball as our national pastime. The National League, sometimes referred to as the senior circuit and the first major league, was formed in 1876. The National League’s first successful counterpart, the American League, evolved from the minor Western League, and was established in 1901. The two leagues, each with eight teams, were rivals that fought for the best players. The World Series, pitting the two major league champions against each other, was inaugurated in 1901. The game is virtually unchanged today from the rules established in 1901.

SUDA DOCKYARD, CRETE, IN 1897.

Baseball Today

Baseball is our national pastime. The rules have essentially remained unchanged for the past 125 years. One notable change is the designated hitter rule in the American League in 1973, and which the National League adopted in 2022. Game strategies have changed markedly from hit and run, to power hitting, and relief pitching plays a much bigger role than it did a half century ago.

That said, in response to baseball fan’s complaints that the game takes too long and is unexciting (at least when compared to NFL football), MLB instituted the following changes over the past five years:

1. Pitch timer. There’s a 30 second timer between batters and a pitch clock limiting pitchers to 15 seconds to throw a pitch (20 with runners on base) and hitters to be in the batter’s box within eight seconds. Penalties will be assessed as an added ball or strike, respectively.

1a. Pickoff/step-off limits. In order to entice more stolen base attempts and to speed up play, pitchers are limited to how often they can make pickoff attempts or step off the rubber. Penalties could include a balk.

2. Defensive shift restrictions. Since it had become common for teams to shift their players to load either side of the field to defend against pull hitters, new (somewhat complicated) penalties were invoked.

3. Bigger bases. To add safety for both runners and fielders, the infield bases have been expanded 44% (15 to 18 inches square). Home plate remains unchanged. The primary goal is safety, giving players more room to operate without colliding.

4. A more balanced schedule. Every team will have at least one series against every other team. This fits with the expanded (2020) postseason format with three Wild Card spots in each league. A more balanced schedule limits the advantage a weak division team has over a strong division team in the Wild Card race.

5. Faster replay reviews. Instead of ten seconds, managers must immediately hold their hands up to signal they are considering a challenge. The umpire will initiate a 15-second (reduced from 20) timer, wherein the manager must decide whether to pursue the challenge. Each team will have one unsuccessful challenge per game.

6. Position player pitching limits. Previously, a position player could appear as a pitcher only in extra innings or if their team was trailing or winning by at least six runs. Now, a position player can only enter as a pitcher if the game is in extra innings, their team is trailing by at least eight runs at any time or their team is winning by ten or more runs in the ninth inning. These restrictions don’t apply to players who qualify as two position players.

7. PitchCom. The system was introduced in 2024 to speed up the relaying of signs between the catcher and the pitcher. The catcher would input the call on a wristband device which the pitcher would hear via a receiver in his cap. Now, the pitcher can call the pitches with the catcher hearing them in his helmet. At any time, two transmitters are permitted to be in use on the field (one for the pitcher, one for the catcher); and up to five receivers in total can be worn by the defensive team.

8. Automatic runner in extra innings. When a game goes into extra innings, the team at bat will place a runner on second base to facilitate breaking the tie. No regular-season game has gone longer than 16 innings since that rule change took place. The rule doesn’t apply in Postseason play.

In closing…

As a child, I remember going to my first game mesmerized by the imagery. We were out in the stands, the sun on our faces, and the crowd’s buzzing with anticipation. Every pitch, hit, and catch felt like a mini-drama unfolding right before your eyes. And let’s not forget the camaraderie of sharing those high-fives with strangers, as your team scores a home run. It’s an instant connection.